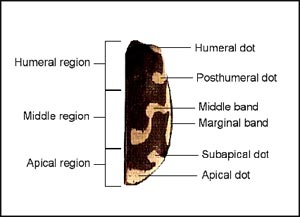

Identifying a Tiger BeetleThe name “tiger beetle” describes members of this group not only in their predatory habits and agility, but also in the distinct pale markings that adorn the elytra (wing covers; modified forewings) of most species. Combined with the general color of the dorsal surface, these markings are most often diagnostic to the species and even subspecies level. These markings (maculation) can be delineated into distinct regions of each elytron in many cicindelid genera, most notably the genus Cicindela. Because all but three of Nebraska’s tiger beetle species are members of this genus, and the other three are relatively easy to identify, the following diagram is only meant to apply to the genus Cicindela. Right elytron of Cicindela repanda

Each species typically has maculation that follows a specific pattern, but as occurs in any species, there can be a great deal of variation, especially in the extent of maculation. But as traits such as color and structure in any organism are largely dictated by genetics, and natural selection has led to specific maculation patterns that have made each species successful, the general shape of the maculation only varies within certain limits. Knowing this, it is then no surprise that as species such as Cicindela sexguttata may have anywhere from zero to four whitish dots on each elytron. At the same time, any one of these dots, if present, will typically always occur in the same general location. The sculpturing of the elytral surface can also be diagnostic. Those species with a coarsely sculptured elytral surface tend to have a duller luster, while those with shooth sculpturing will have a more greasy or shiny luster. Thus though C. sexguttata and C. denverensis are both green dorsally, the sculpturing on the dorsal surface of C. sexguttata is much smoother, giving it a much shinier appearance. In order to avoid too many technical terms, the descriptions of appearance for the Nebraska species are based only on easily visible dorsal features, most notably coloration and markings. Life HistoryThere are two general life history patterns among Nebraska’s tiger beetles. Species referred to as spring-fall active emerge from the pupal stage in late summer and fall. Though many are active for a few weeks shortly thereafter, a few others remain underground through the winter. In either case, the winter is spent as an adult beetle underground. Activity resumes in spring or early summer, and reproduction occurs during this period. A rare exception among North American species is C. nigrior of the southeastern United States, which apparently completes its entire reproductive cycle in fall. Species like C. splendida, C. denverensis, C. limbalis, and C. purpurea become active shortly after snowmelt and are often gone before June. Others, like C. formosa and C. sexguttata do not begin to appear until at least the end of April and remain common well into summer. A few species, such as C. repanda and C. hirticollis are particularly long-lived as adults, and through they may begin to appear in March and April, many adults may survive well into July and even into August. In these species adults may be found commonly throughout the warmer months, as the cohort of one year may overlap with the fall activity period of that of the following year. Summer active species emerge from the pupa in early and midsummer, and reproduce and die before winter. The life span of the adults is variable, and species like C. lepida often live for only a few weeks, while species like C. punctulata may survive for several months. The larvae of all tiger beetle species are sedentary sit-and-wait predators. For most species, the entire larval stage is spent in a burrow within the ground. The orientation of the burrow is vertical for the most part, and the opening is normally perpendicular to the soil surface. The lone exception to in Nebraska is C. formosa, whose larval burrow is mostly vertical, but has an elaborate opening consisting of a pit with the burrow opening horizontally above it. The larvae spend most of their time waiting at the top of the burrow for prey to pass close enough to be captured. The unique anatomy of tiger beetle larvae allow them to behave like a jack-in-the-box, catapulting the front of the body at the prey while anchoring the abdomen in the burrow. Because of their predatory nature and the general rarity of meals, the larval stage of all Nebraska species requires from one to three years of development. Though larvae of C. hirticollis are known to frequently abandon burrows and move to dig new ones in response to changing moisture conditions, the larvae of most species spend their entire larval development at the same location in which the egg was initially laid. Tiger beetle larval burrows are often very numerous in proper habitats, and many a beachgoer would likely be astonished to know of the hundreds or thousands of these little beasts lurking beneath their feet. Because the larvae are skittish, it is rare to actually see one at the top of the burrow. However, if a person is patient, they may be lucky enough to see a larvae return to the top. The depth of the larval burrows varies not only by species, but also by local conditions. In Nebraska, the depth of C. formosa larval burrows may vary from 50 to 100 cm, and the depth appears to be somewhat related to soil drainage. The larvae go through three stages of development, each of which is called an instar. In tiger beetles all three instars look pretty much alike except that the general body size in each instar is approximately double that of the previous. Because of the fact that most Nebraska tiger beetles are between 10 and 18 mm in length and the size of the larva changes dramatically with each instar, it is easily possible to determine the instar of a larva by the diameter of the burrow. Molting from one instar to the next is facilitated by feeding until a threshold body mass is attained. Pupation occurs at the end of the third instar. Tiger beetle larvae can be captured by a number of methods. For species with deep burrows it is best to insert a long grass blade into the burrow and then dig a hole adjacent to it. The burrow can then be slowly excavated from the top down without losing track of where the burrow goes. The larva will most often be at the bottom of the burrow. The stab and grab method involves waiting near the top of the burrow with a garden trowel and waiting the larva to appear at the top of the burrow. Because the larva will often drop to again to the bottom of the burrow immediately if alarmed, it takes quick reactions. The trowel must be quickly inserted at an angle into the ground below the larva, cutting it off from retreat, but leaving it unharmed. The third method is called fishing. Most species with vertical burrows can be easily collected with this method, but it takes practice. A thin grass blade is inserted to the where the larva causes resistance. The blade is the move enough to agitate the larvae into biting it. Once resistance is felt, the larva can be quickly pulled out of the burrow. As with the stab and grab method, this requires much practice. Though this method is fast, it does not work well for species with curved or bent burrows, or timid species like C. cursitans.ConservationA number of tiger beetle species have become rare in recent decades. In a few cases, species that were previously common have disappeared from vast areas. In most of these cases humans appear to be at fault. Some of the biggest culprits for the decline of many Midwestern species are excessive beach traffic, dams and other water alterations, off-road vehicles, natural succession, and habitat loss to agricultural and urban expansion. The most familiar rare tiger beetle to most Nebraskans if the Salt Creek tiger beetle (Cicindela nevadica lincolniana). This insect never had an expansive range and has, in fact, never been recorded outside Lancaster County. This limited distribution makes it especially vulnerable to extinction. There are other species with broad distributions that have suffered severe declines. Cicindela lepida has been recorded from a number of locations across Nebraska, but recent surveys suggest that it may be nearly eliminated from the state. It also appears to be in severe decline throughout the Midwest. Cicindela hirticollis has not experienced a major decline in Nebraska, but has disappeared from much of its former distribution across North America. Cicindela celeripes was once known to be not uncommon in parts of the state, but it has not been found in the state since 1915. Currently, only two good population centers are known anywhere among collectors and researchers. For each of these species, there appears to be a single most important factor in the decline. For C. lepida the decline might be the result of natural succession; however, much apparently suitable habitat still exists within the state, and the effects of artificial lights may be more important (This species is highly attracted to lights at night.). For C. hirticollis the primary factor appears to be alterations to the ecology of waterways. For C. celeripes, the primary factor is most likely habitat loss to agricultural expansion and invasion of bluff prairies by woody vegetation. Because of the specificity of each species to a specific habitat type and their sensitivity to habitat change, tiger beetles have recently become relatively popular ass biological indicator species. Thus the loss of a species within a given habitat type across a broad region may indicate habitat alterations that could also be affecting species of other taxa as well. This pattern can be seen in Cicindela hirticollis. It is common to find this species occurring in the same areas as the federally endangered piping and snowy plovers (Charadrius melodus, Charadrius alexandrinus) in different parts of its range. Though the beetle can be found where the plovers are lacking, it is rare to find the plovers without the beetles except in dry areas. Therefore it is likely that the bird and tiger beetle have similar habitat requirements, and the beetle may be a good indicator of suitable plover habitat. |